elibaum.com

[not so] fire computer

11 May 2024

Update 13 May: Steve Mould pointed out that property 3, below, is not actually true! I rewatched the video and, indeed, there are some clear counterexamples of property 3 (for example, the split-merge racetrack). So, we can NOT build a computer. See below for some further thoughts.

Steve Mould put out a video a few weeks back describing a neat effect: vaporized lighter fluid in a perfectly-sized channel allows a flame to travel down the channel, almost like an electrical pulse.

In the comments, Steve said he didn’t think you could use this to build logic gates, and therefore probably no fire computer. But I think we can build logic gates, and thus yes fire computer. Another commenter referenced the Wireworld Computer, which, while having slightly different cellular-automata rules, served as good inspiration.

the rules of fire

First, a slightly idealized mental model of the traveling flame.

- A flame will travel along a channel at a fixed speed.

- A flame approaching a branch will split and continue. For reliability, let’s say we never have more than a four-way intersection.1

- A flame approaching a branch forming an acute angle (with respect to its own direction of travel) will continue straight and not return down the acute branch. (By property 2, a flame traveling in the opposite direction will split.)

- Two flames traveling in opposite directions will cancel each other out when they meet.

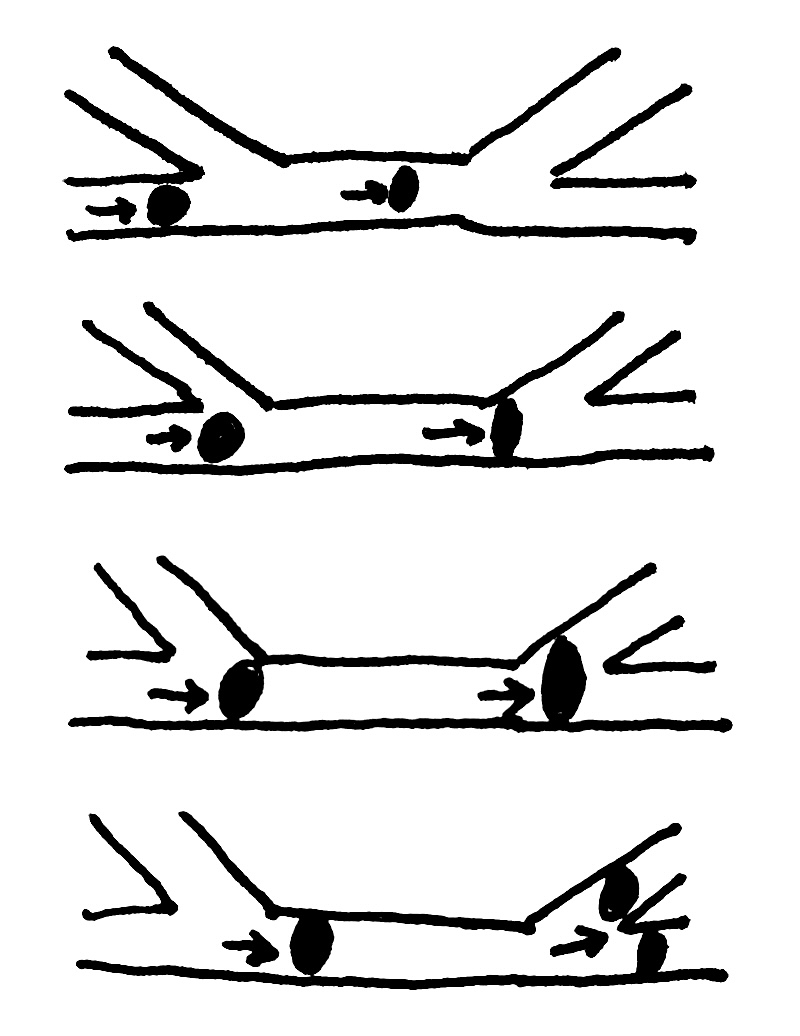

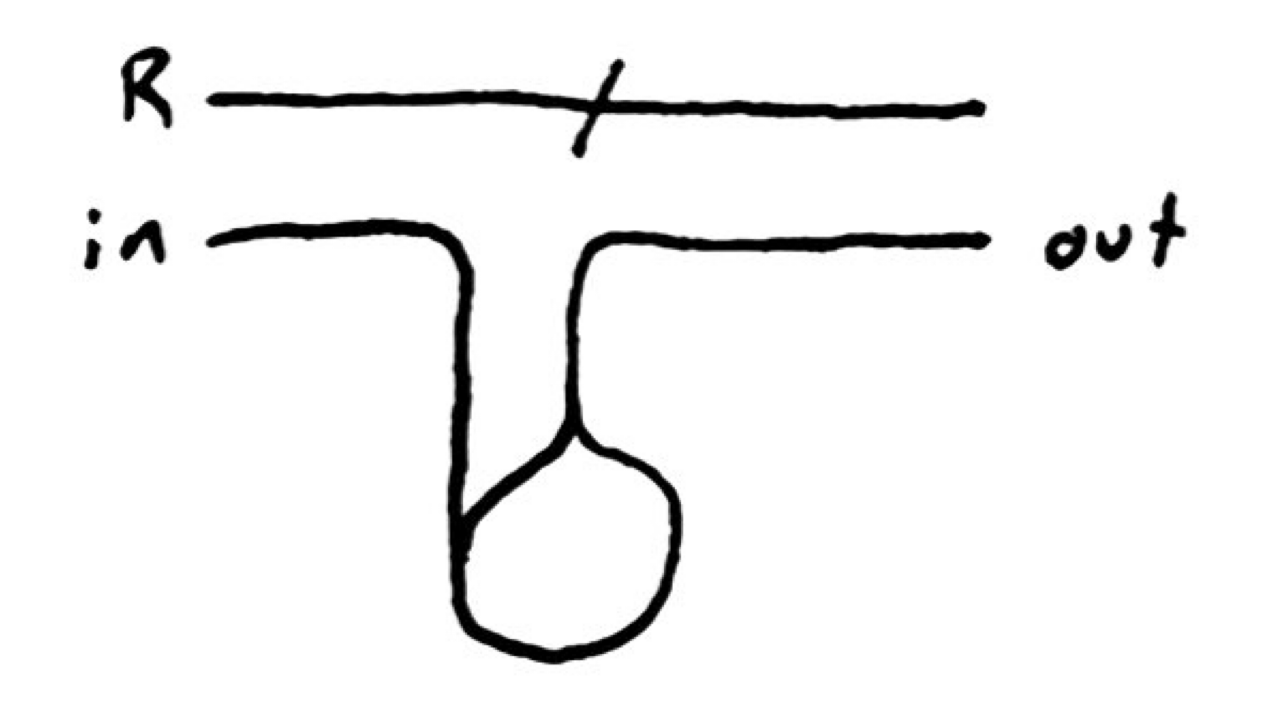

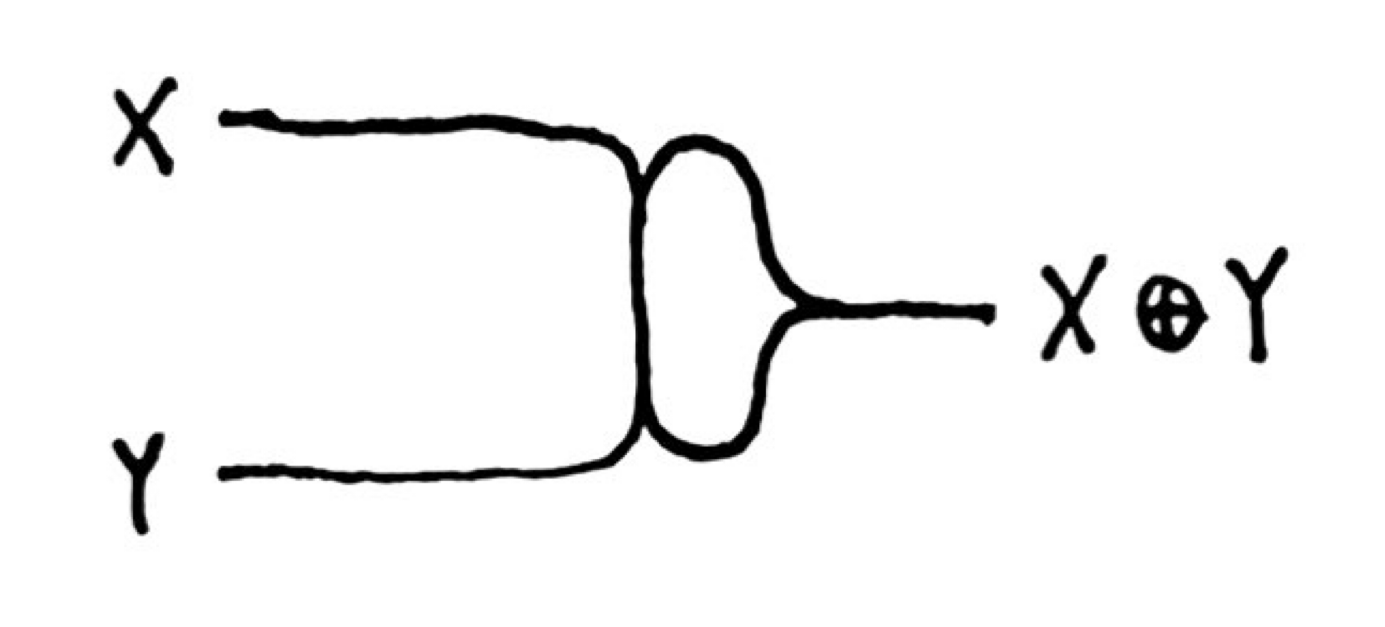

To illustrate properties 2 and 3 a bit better:

Pulse on the left does not travel backwards up the left branch. Pulse on the right splits in two.

Pulse on the left does not travel backwards up the left branch. Pulse on the right splits in two.

I don’t have easy access to a 3D printer, so I won’t be able to confirm these are all correct. I would love to hear about any attempts to test out these theories.

Since a traveling flame cannot be statically persist, to have any notion of a signal, we need a clocked system. We’ll assume some sort of “ready” channel (or you could think of it as “power”). Pulses in the ready channel will correspond to the existence of a signal, whereas pulses in other channels will represent data. I’ll refer to signals as being “hot” if they are on fire.

building logic gates

wire

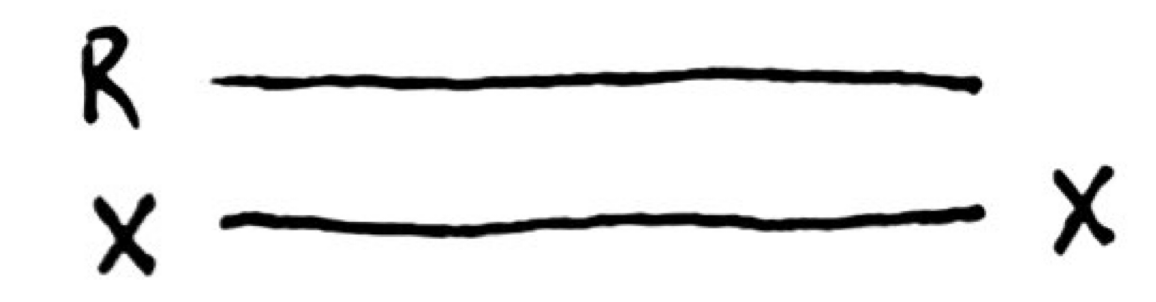

The simplest gate is the identity. That’s just two channels, one power and one data.

not gate

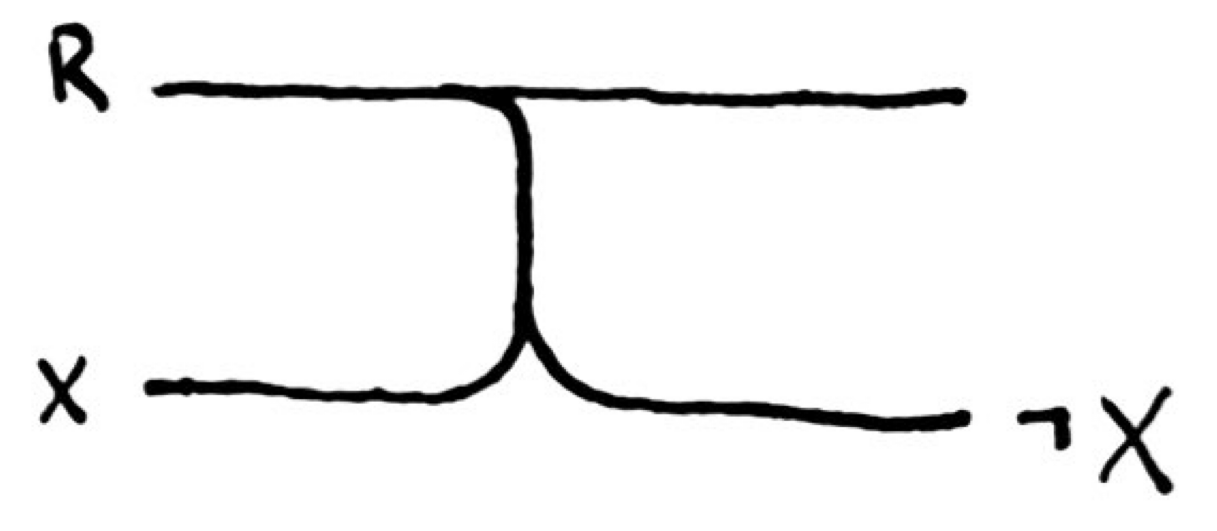

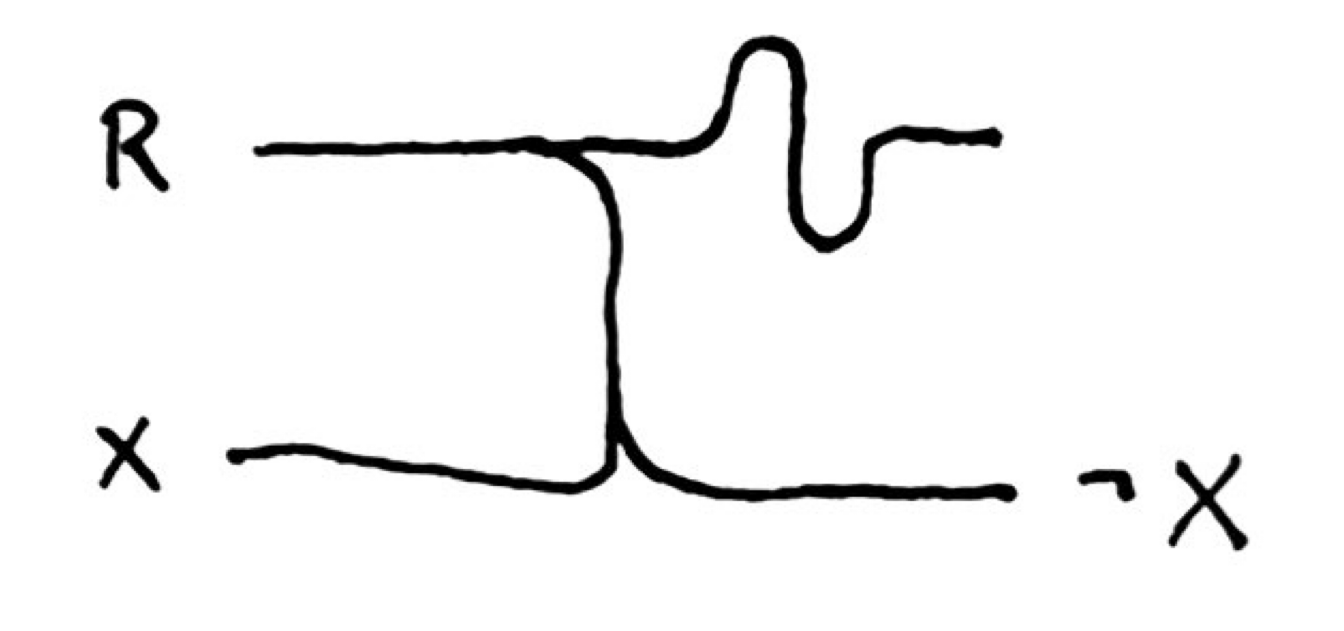

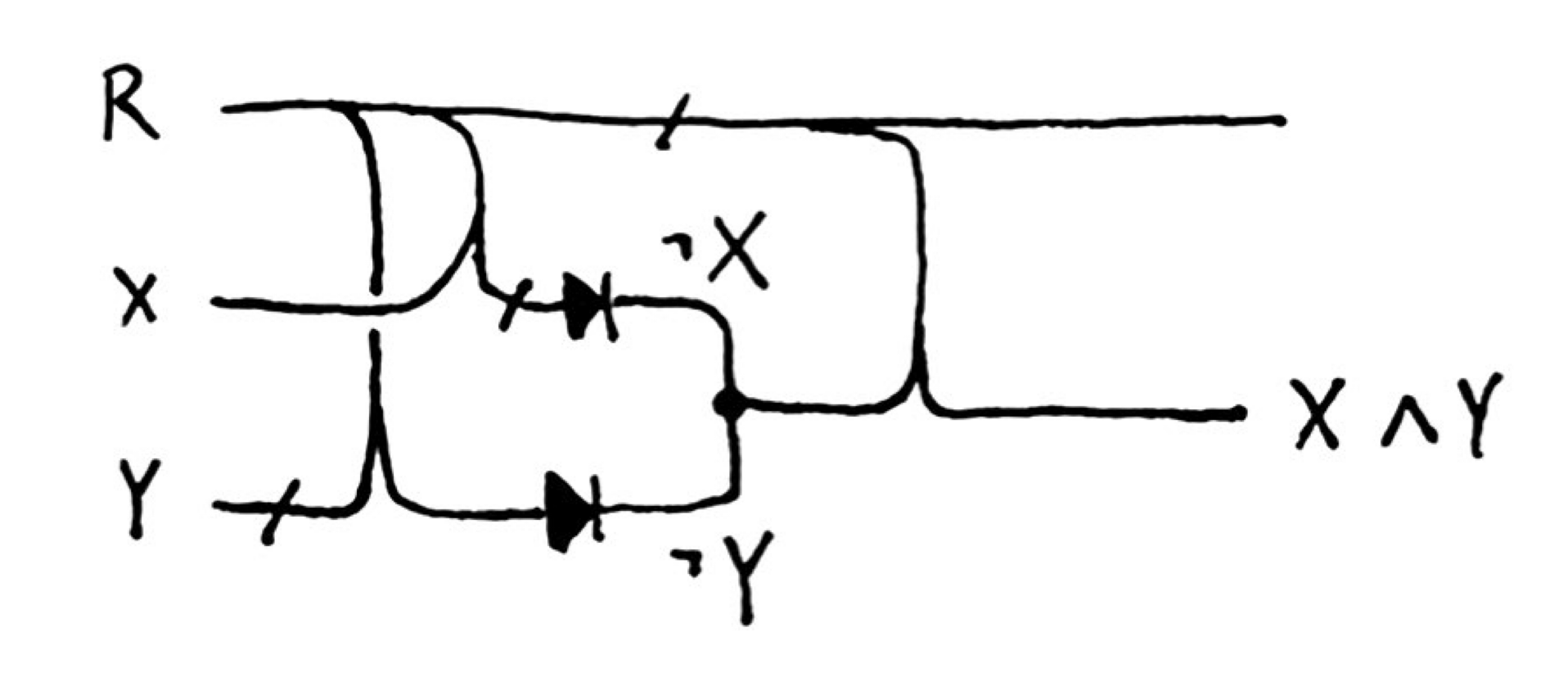

To invert a signal, we apply the cancelling property: split the power signal, then route it such that it will cancel a data signal. If there isn’t a data signal, however, the split clock signal continues on to the empty data line as a new signal.

An inverter might look something like this:

Ris the “ready” channel, and it signifies when a signal exists on the corresponding data line. In some of the diagrams below, I have dropped theRsignal, but assume it always exists and is of the proper length to align with the data output.

An inverted signal will take a bit longer to reach the output than R. So, in reality, we need to stretch R by the appropriate amount:

But I’ll stylize this with a hash, to signify that a wire should be stretched to the “proper” length.

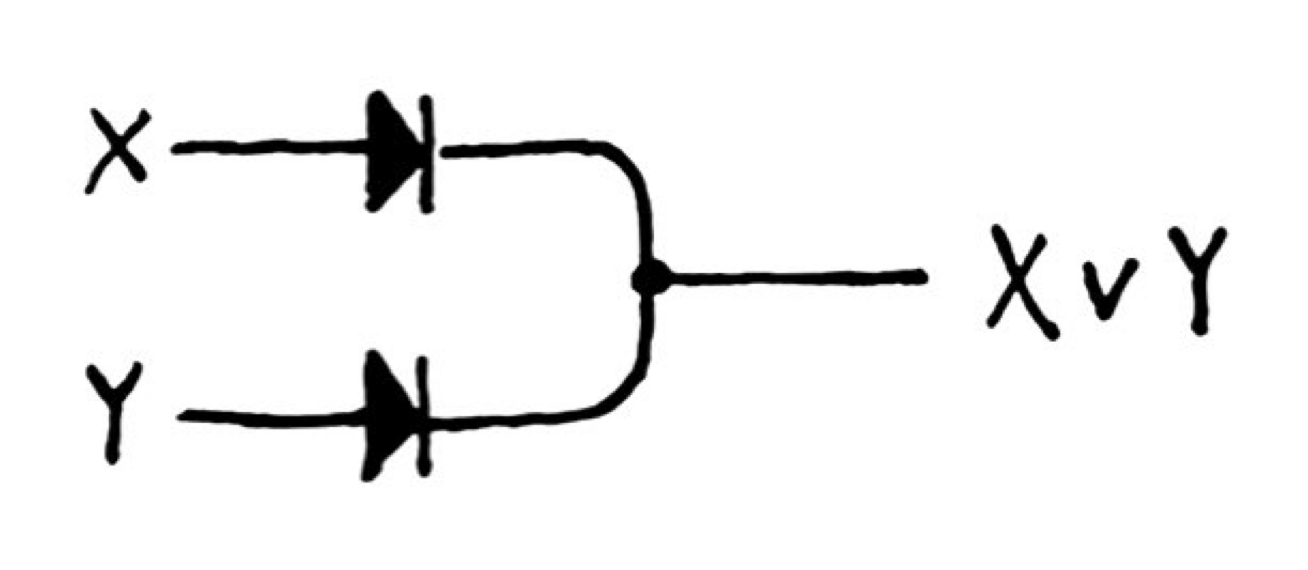

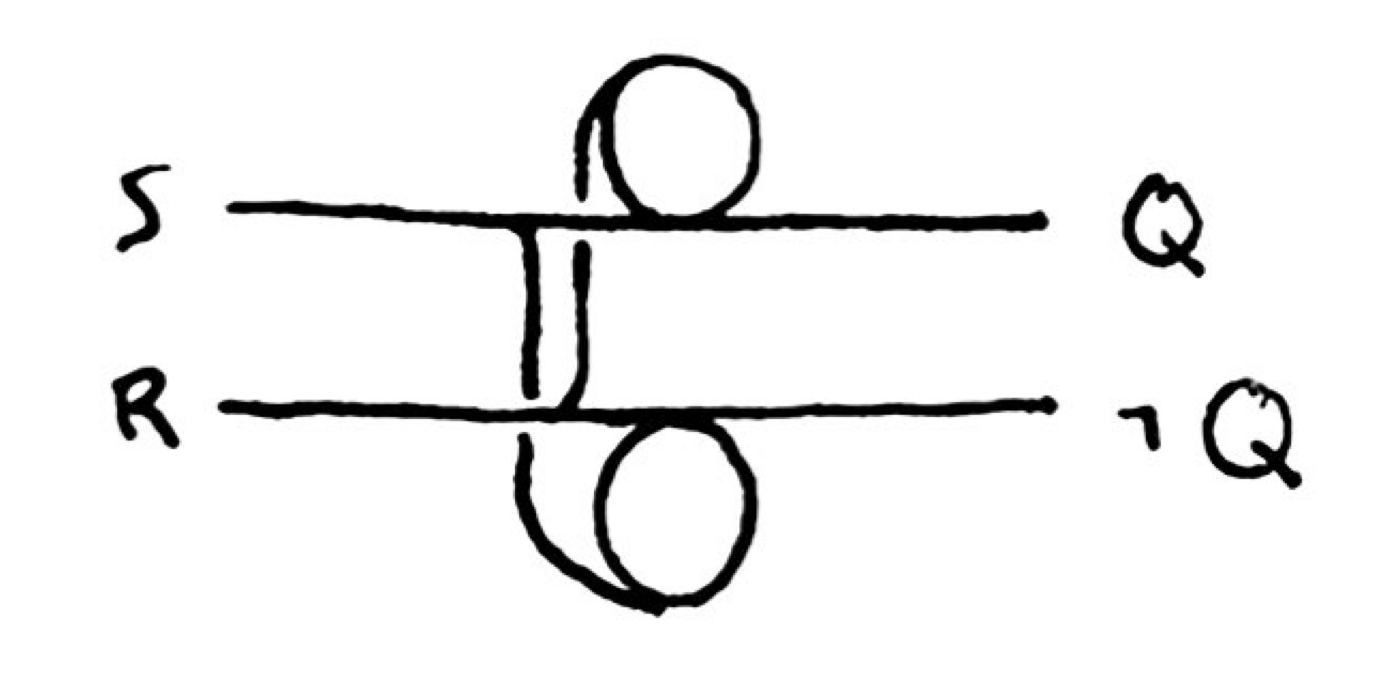

diode

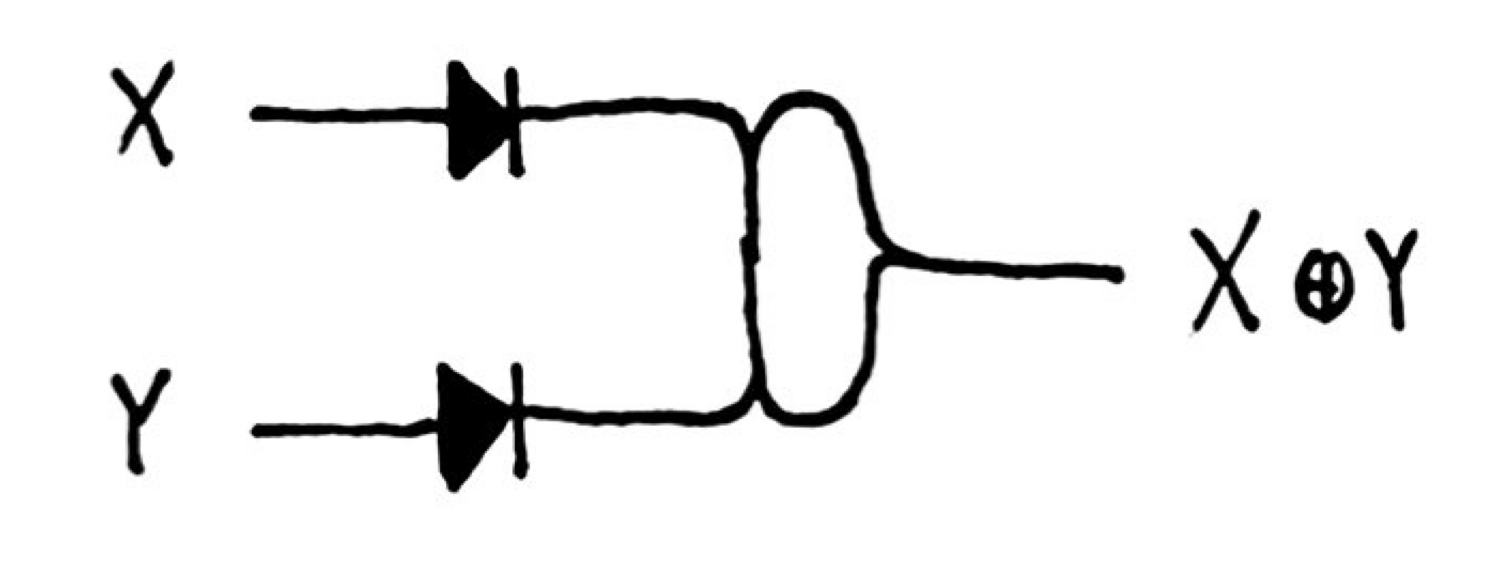

Next, we’ll need a diode, to prevent backpropagation of flames. Here’s my idea:

Signals coming from the left (the forward direction) travel around the perimeter of the loop and exit. However, signals from the right split at the loop and cancel each other out at the bottom. Due to the angle of the inbound line, these signals will not travel back to in, by property 3.

Of course, this diode has a maximum switching speed: it can’t handle signals coming from both directions particularly well. As we will see below, the other gates do not intrinsically prevent backpropagation, which could occur even in normal circumstances. So I think copious use of diodes will be required to have a somewhat reliable circuit.

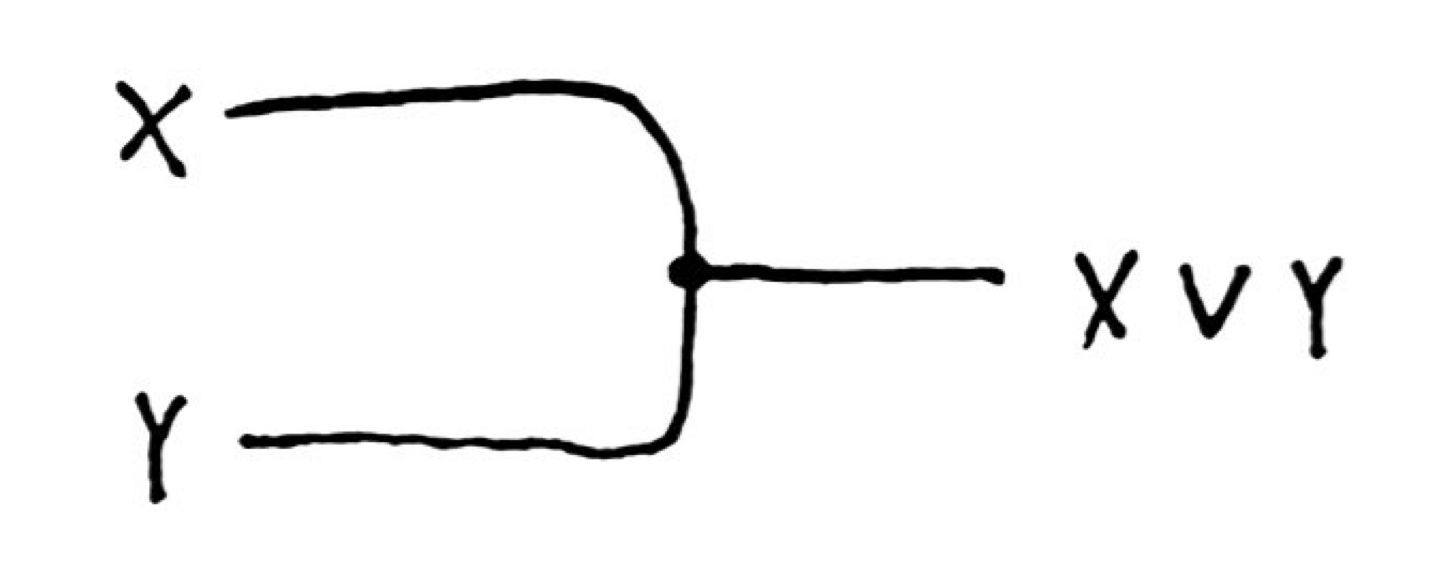

or gate

This is pretty simple: we just connect two wires in a T.

A signal coming from either X or Y will split at the shared node and produce an output. The case where both X and Y are hot is a bit more interesting: the flames will cancel at the shared node, but (I believe) will also allow an output flame to progress.

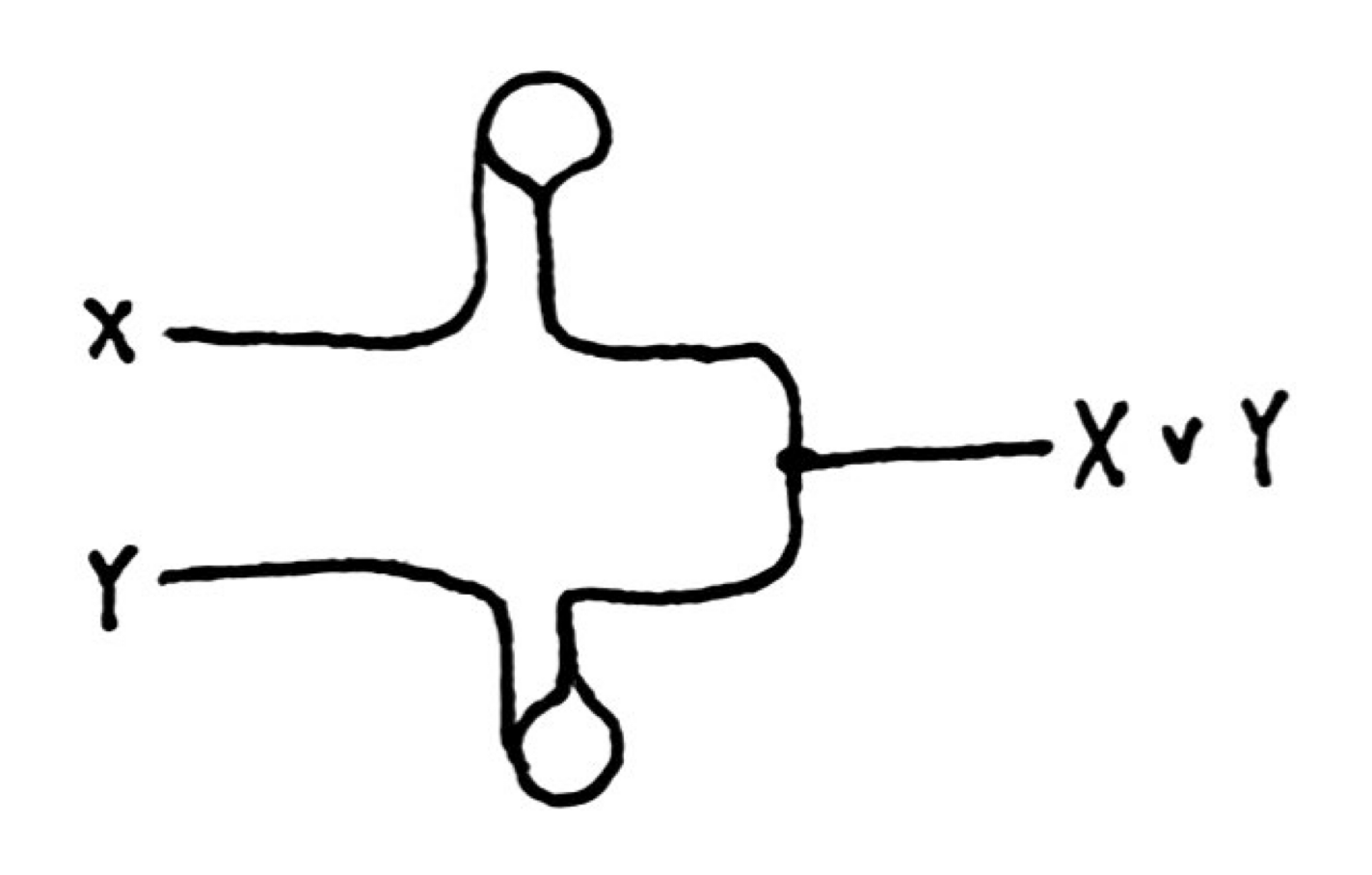

We do need to be careful of backpropagation here. With a single hot input, that signal will split towards the output, but will also continue back towards the other input. So, to make a reliable OR gate, we need diodes:

I’ll simplify this using the standard circuit symbol for a diode.

xor gate

This is similar to the OR gate; we just need to prevent the double-hot case from producing an output. To accomplish this, we move the output connection away from the center node. If X ^ Y, the signal travels around the extra loop and creates an output. But if both inputs are hot, they cancel in the middle, never reaching the output loop.

Of course, we should also have diodes here.

full basis

And that’s it! We now have the tools to make a computer. We can implement an AND gate, for example, with three inverters and an OR gate:

The hashed wires in this gate should be resized so all signals arrive at the same time.

the rest

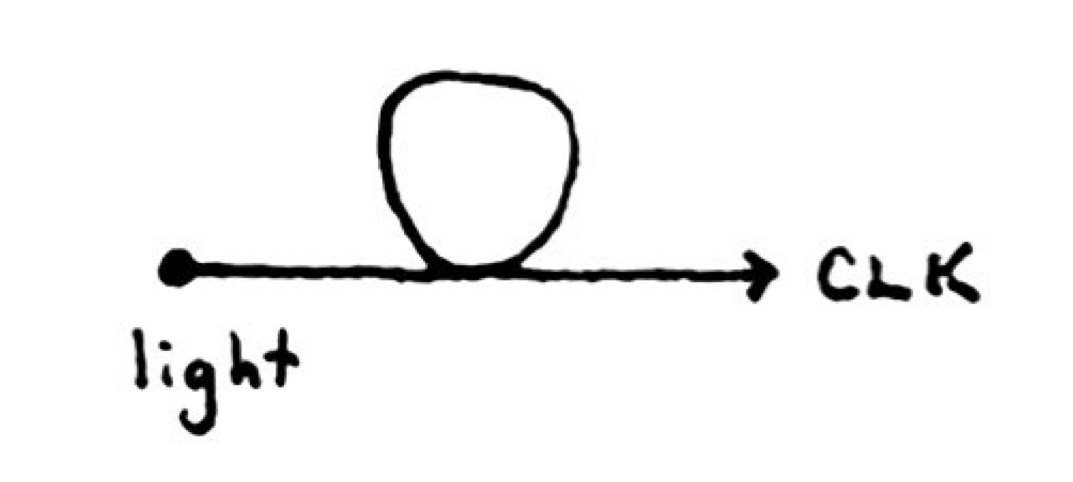

We might also like a clock generator, which we see in Steve’s video. Varying the diameter of a loop affects the frequency of the clock generator. Assume you light the circuit at the left-hand node (since, per the video, it’s tricky to light a loop on its own).

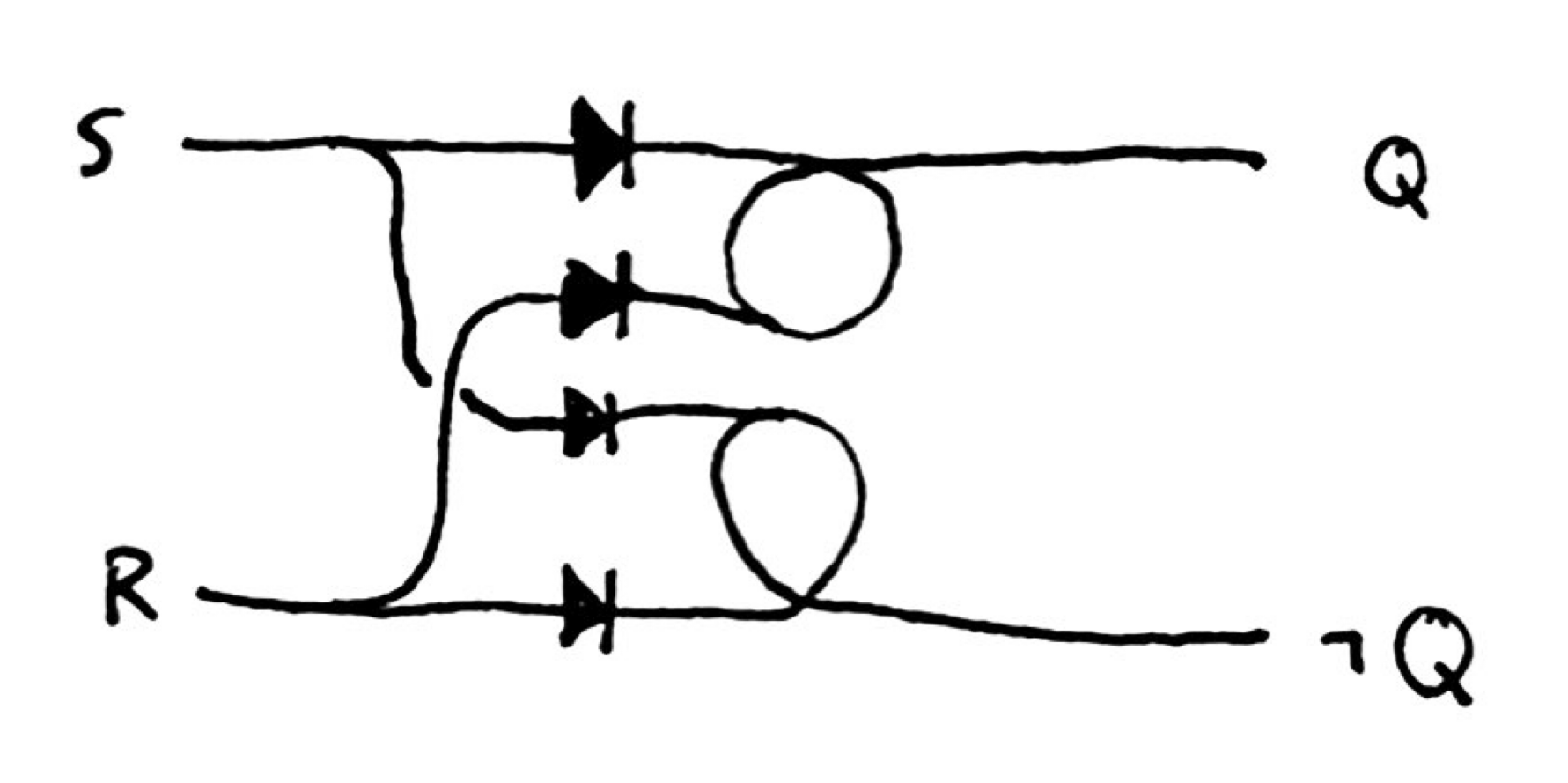

Two clock generators give us a (pulsed) latch:

Though, again, we need diodes to prevent backpropagation.

Unfortunately, there is a bit of a race condition here, since each active clock will send pulses into the diode. The “reset” pulse will need to travel from the diode into the clock loop before any such clock pulse resets it on the diode branch. This can be mostly avoided if the clock frequency is low and the diode is very close to the loop. We may also be able to send a series of pulses to ensure at least one pulse makes it through and disables the clock.

prior work

The underlying phenomena here, as Steve mentions, is something known as “excitable media.” It seems like building circuits in excitable media is actually a relatively well-studied phenomena, though mostly with respect to chemical reactions.

Rössler 1974 appears to be one of the earliest works on this matter2; Tóth and Showalter 1995 considered the design of logic gates in a specific chemical reaction. Motoike and Adamatzky 2005 considered circuits built under a tri-state model (true, false, “nonsense”), which allows for more expressive designs in what is fundamentally an analog medium.

So it seems like — at least in principle — you could build a computer out of fire. Dealing with spurious ignition, timing issues, and lighter-fluid refills are left as exercise to the reader.

addendum

(13 May) So, no property 3. This is unfortunate and basically breaks my entire construction. Steve brought up another idea for building a diode:

Someone suggested a track that abruptly changes in height. A flame travelling towards the “cliff” from below would be able to ignite the vapour on the track above, but a flame approaching the cliff from the top would not be able to light the vapour from the track below. And so we have a kind of flame diode could potentially make all these things possible. I haven’t tried it though.

Let’s assume this works. What can we do with diodes? Unfortunately, still not much: OR gates are easy; the same idea as above works. But we can’t build an inverter. The Wikipedia article on Diode Logic sounds the death knell:

An active device … is additionally required to provide logical inversion (NOT) for functional completeness…

And it is far from evident to me that we can actually build an active device with the flames! Looking back through some of the chemical work I cited above, it seems like they need to do some tricks with wave properties to get an active device, so maybe it’s still possible, but would require careful analysis and experimentation.

Thinking a bit more about why my original idea doesn’t work: consider the minimal functionality we need for a NOT gate. Signals from the left only travel up; signals from the top only travel to the right. We can ignore signals input from the right for now. And now this starts to sound a lot like an RF Circulator, a particularly clever piece of radio-frequency equipment that, well, provides precisely this functionality.

So, if we could build a fire-circulator, then we get NOT gates, and thus functional completeness. Unfortunately, I don’t have any ideas for how to do this right now.

-

With too many branches, the intersection itself becomes quite large in area, and thus might not be able to hold enough vapor for the flame to persist. ↩

-

Rössler later protested the Large Hadron Collider for fear of it creating miniature black holes. ↩