elibaum.com

a wrigley mystery

04 Aug 2024

Earlier this summer, while in Chicago, I took one of those riverboat architecture tours. You can learn a lot about the city from the river; unlike many other cities I’ve lived in, which feel like they were merely built alongside a river, you really get the sense that Chicago was fundamentally built around the river. All those bridges! Anyway, it’s a great tour.

But there was something that stuck out to me: as we putter past the Wrigley Building (built by the eponymous chewing gum magnate a century ago for his corporate headquarters), our tour guide points out its twin towers and the 14th-floor walkway connecting them. This, she says cheerily, was constructed to comply with a Chicago law against branch banking.

What?

Then everyone presumably forgets about it as we move on to the next architectural landmark. But I stewed: what is branch banking? Why would it be banned? How does building a walkway get around such a restriction? Anyway, there was also a third-floor walkway. This had the definite aroma of a slightly-too-convenient fun fact. Admittedly, it’s a bit of a silly question but I was too curious to drop it.

branch banking

After a bit of Googling, I stumbled across a helpful report from the Chicago Fed which answered my first question. The authors summarize:

The state of Illinois was one of the most restrictive bank branching states in the country. It was what is known as a “unit banking” state in which each bank was allowed to operate only one office. The state constitution of 1870 prohibited branch banking, and that prohibition remained in place until the mid-1960s. The first revision, adopted in 1967, allowed a bank to operate one additional drive-up facility within 1,500 feet of the unit bank. By 1985 banks were allowed to have up to five offices, two of which could be in other counties if they were located no more than ten miles from the head office. Finally, in 1993, the limitations on interstate branching were completely removed; for the first time Illinois banks were allowed to branch freely within the state. These laws applied both to national banks chartered by the federal government and to state banks chartered by the individual state regulatory agencies.

(And thus, this relatively late switch to branch banking, followed by a series of mergers and acquisitions, explains the surprising abundance of bank branches in Illinois today.)

Immediately, you can begin to see the fuzzy shadow of a narrative:

- Bank opens office in Wrigley Building.

- Bank wants to expand but doesn’t want to move.

- Bank buys adjacent property in other tower.

- Bank finances construction of walkway connecting two properties, so that technically they are only operating one office.

But this didn’t sit well with me: wouldn’t you just buy more property downstairs? Would building a walkway really have satisfied the rules against branch banking? Or maybe a bank merger occurred?

timeline

I know this much:

- September 1921: South (riverside) tower completed

- May 1924: North tower completed

- sometime in between: 3rd floor walkway built

- 1931: 14th floor walkway built

some clues

This justification for the 14th floor walkway appears to be a popular fact about the building, but never with any citation. Wikipedia asserts:

In 1931, another walkway was added at the fourteenth floor to connect to offices of a bank in accordance with a Chicago statute concerning bank branch offices.1

The Chicago Architecture Center agrees:

In order to comply with laws against branch banking in Illinois, the 14th-floor bridge between towers was constructed to link two bank offices.

(This is one of the rotating facts on the linked page.)

The city erroneously claimed in its landmark designation that the walkway connects the 16th floors, but doesn’t mention a rationale for its construction.

At this point I had found very little mention of a bank even operating out of the Wrigley building, so I started to look more into that.

(national) boulevard (bridge) bank

A news story from the building’s opening mentions a certain “Boulevard Bridge Bank” which appears to have been one of the founding tenants of the building.2 Mentions of the bank dot the internet:

- A book of marble buildings places the Boulevard Bridge Bank in the south tower, alongside Wrigley’s head office. (p. 36)

- Vintage piggy banks commemorating the Wrigley Building show up for sale on eBay.

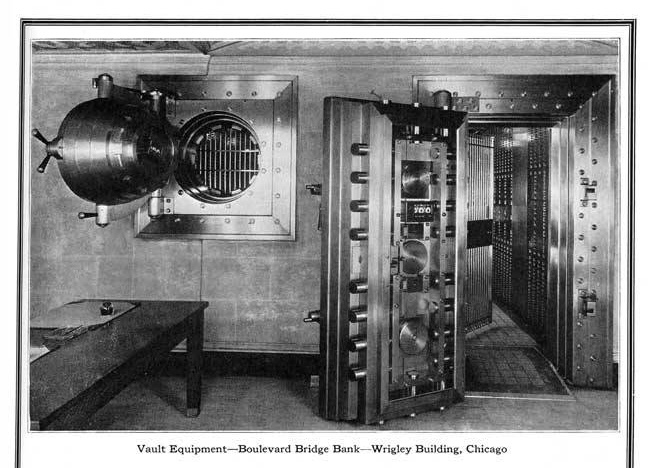

- The Art Institute has a photo of the vault, but we know from the above news story that this was in the basement, implying the bank probably operated of the lower floors…

After that, I couldn’t find much else about the walkway, let alone Boulevard Bridge Bank. But this does seem like it must be the bank in question. For more information, I turned to a significant untapped resource: the newspaper!

old news

The Chicago Tribune’s offices sit just down the block from the Wrigley Building. I thought I might be able to dig something up from their archives.3 Indeed, here we begin to find a… sticky answer to our mystery!

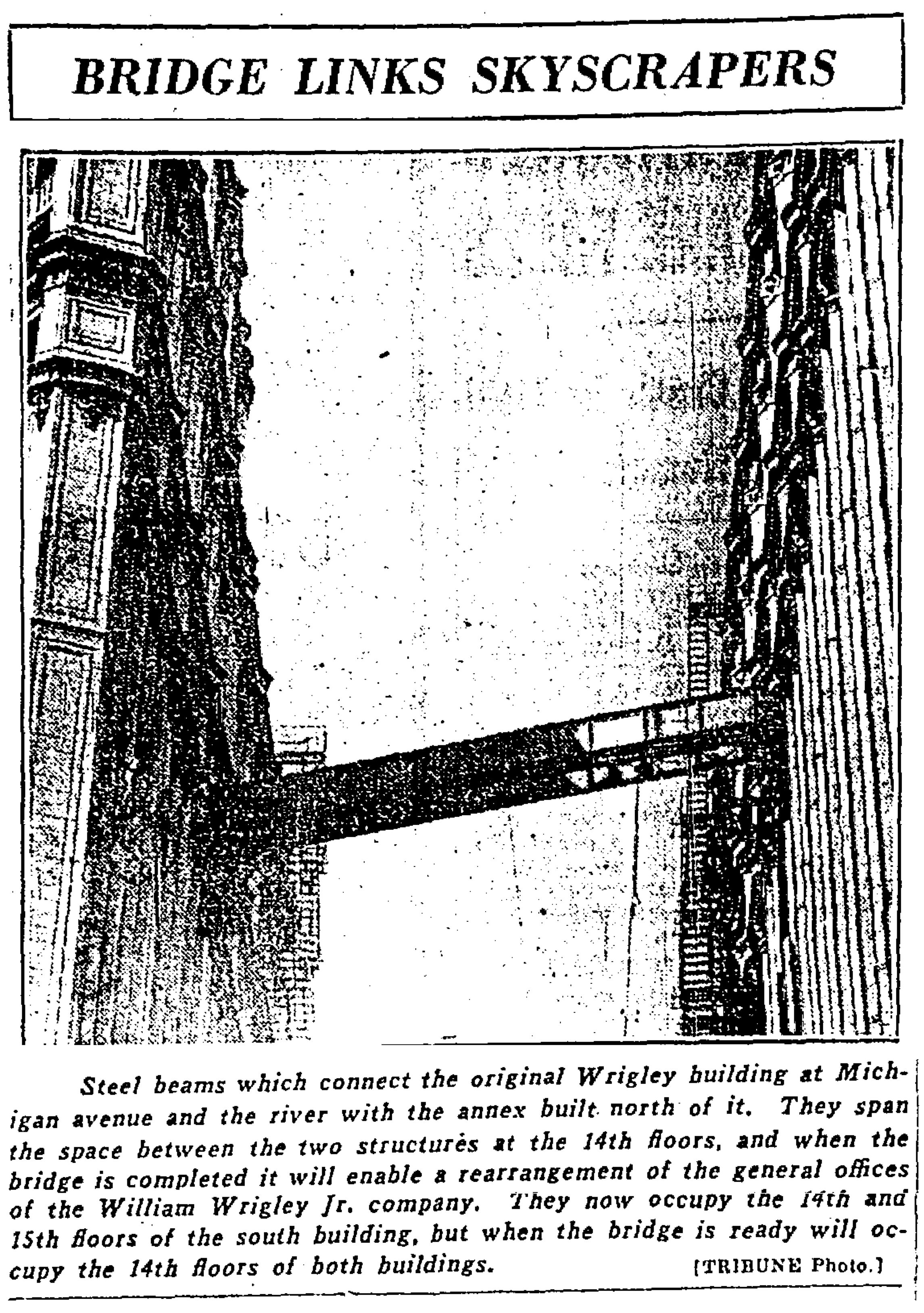

- Aug 30 1931, p. 10: “A bridge … is being built on the 14th floor level … to connect the general offices of the William Wrigley Jr. company.” (emphasis mine) The offices were previously on the 14th and 15th floors of the south tower; the bridge would allow the 14th floors of both buildings to be used instead.

- Aug 31 1931, p. 6: “…will enable a rearrangement of the general offices of the William Wrigley Jr. company”

Chicago Tribune, Aug 31 1931

Chicago Tribune, Aug 31 1931

- Mar 29 1933, p. 20: Boulevard Bridge Bank receives US charter and is renamed National Boulevard Bank.4 (This name change explains why I was having trouble finding info on the bank under its original name.)

-

Feb 16 1957, p. A5: More confirmation.

The National Boulevard Bank of Chicago is preparing to expand its quarters in the Wrigley building about 60 per cent by taking over most of the first floor, and a large part of the lower level floor of the north section of the building, O.P. Decker, president, announced yesterday. At present the bank has the entire main and lower floors, as well as parts of the third and fourth, of the south section of the twin towered building.

-

Sep 15 1964, p. C5: “Work Started on Corridor in Wrigley Bldg.”

Construction has started on a heated enclosed corridor between the north and south sections of the Wrigley building which will connect the investment and commercial loan departments of the National Boulevard bank of Chicago. Remodeling and refurbishing of the second floor in the north section of the bank’s quarters also is scheduled, Irving Seaman Jr., bank president, said.

It’s not clear from the article where this corridor is, but I think it’s probably on the ground level, as depicted in this 2010 flickr photo. After a recent round of renovations, the enclosed walkway was removed, restoring the plaza to its original form.

I’m going to say the rumor is FALSE! From these newspaper articles, it seems like Boulevard operated on the lower floors of the building, only reaching the fourth floor by 1957. While the true motive for constructing the walkway may not have been accurately reported at the time, it seems more likely than not that the bridge was merely designed to rearrange Wrigley’s offices. This seems like quite an involved renovation just to move your downstairs neighbors across the way!

My tinhat theory (for which I have zero evidence, to be clear) is that Wrigley, who died in 1932, had become too infirm to use the stairs between the 14th and 15th floors, and wanted all of his employees on a single floor. But they definitely had elevators at the time of construction…

postscript

If you are in the market, the entire 14th floor is, as of this writing, for lease.

And: I have corrected the historical record.

-

I thought maybe the Wikipedia edit history could provide some insight, but this exact sentence was part of the very first edit back in 2002! ↩

-

I now can’t dig up the source where I thought I read this, but it seems like Wrigley started the bank expressly to be the anchor tenant and draw other business to his new skyscraper. ↩

-

With a Chicago Library card, you can access the archives of the last 175 years of Chicago news. ↩

-

National Boulevard was bought 60 years later by First Bank, which continues today as US Bancorp. ↩