elibaum.com

pandemic projects: tiny game of life

25 Mar 2021

I love Conway’s Game of Life, and I had a small OLED display lying around that I thought would be perfect for a tiny Life-in-a-box contraption.

Most of the effort here went into trying to get the code to fit into an ATtiny85 dev board (only 512 bytes of RAM, half of which were required just to store the 64x32 board). But this became quite a headache — I didn’t have a good way of debugging the ATtiny, it was incredibly slow, and I had to reimplement a lot of the Adafruit OLED Graphics library. Eventually, I subbed out a pin-compatible Trinket M0 board, which blew the ATtiny away (48MHz 32-bit CPU; 32KB RAM; only $2 more) and was generally much more of a pleasure to work with.

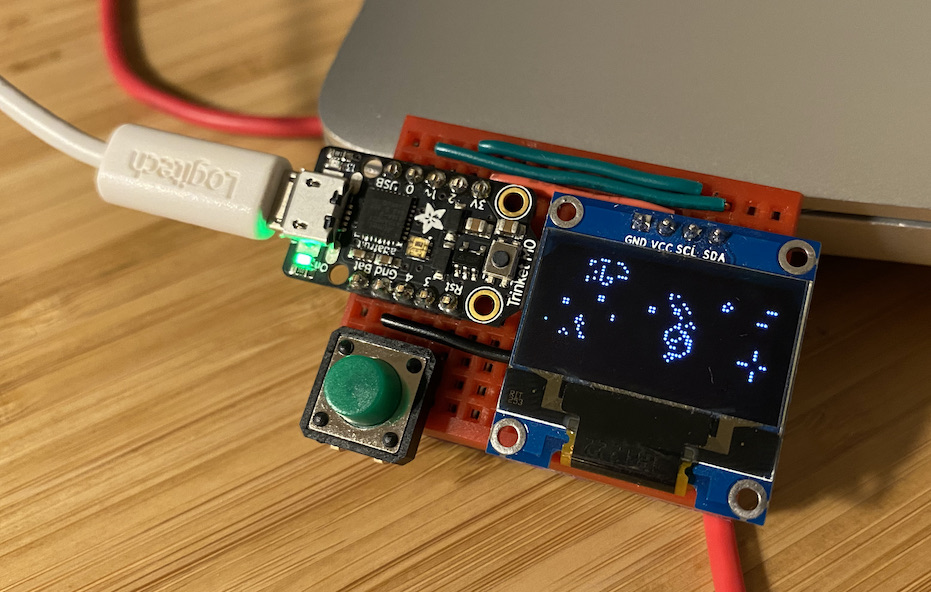

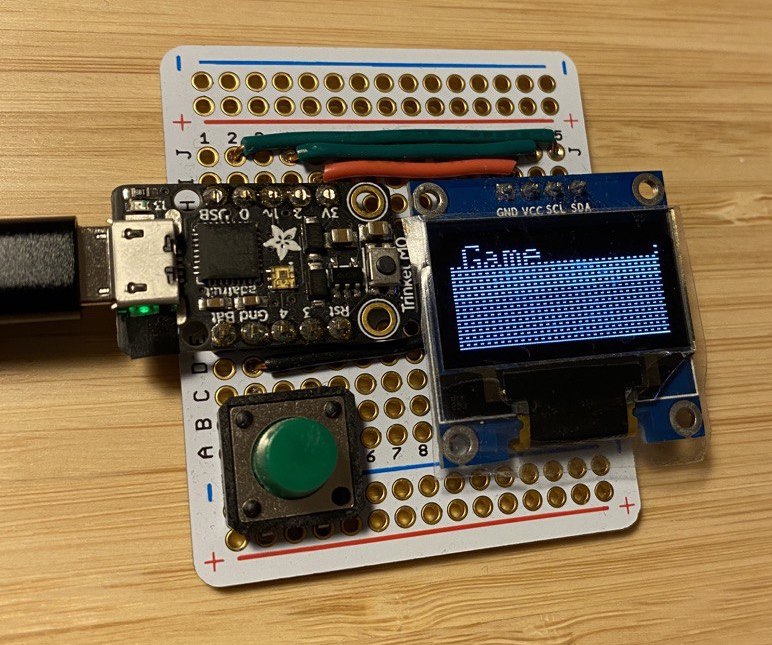

Breadboard prototype

Breadboard prototype

The End of the World?

Once I had a basic implementation working, I had to figure out how to keep things interesting: on a board as small as the one I am running on, complex structures are hard to come by, and most random initial configurations settle into a somewhat boring equilibrium after about a thousand generations. I wanted to figure out some way to detect the “end” of a round, at which point I could reset the board with a new random configuration.

Note that, since Life is Turing-complete, I believe this question reduces to the Halting Problem, so there’s no reason to believe it is easily doable.

My first attempt was to just count the number of alive cells. But this gives a lot of false positives (i.e. gliders moving across the board). Next, I thought about generating a hash of the current state. I settled on djb2a, usually used as a lightweight string hash function, but it did the job here.

Every six frames, I compute a new hash (treating blocks on 8 cells as a byte) and compare it to the last one. If it’s same, we must be in a 2-, 3-, or 6- period oscillation. This covers the vast majority of common cases, according to a “census” of Game of Life oscillators; the most common oscillator, a 2-period “blinker”, occurs with relative frequency 99%.

Besides the occasional (~ 1 in a 1000) case where a glider hits no obstacles and endlessly moves across the board, I have not yet observed a case where this system failed to catch a “stable” board.

Speed upgrades

Once I moved to the Trinket M0, I made a few improvements for speed and clean-code purposes:

-

Since I am now using a 32-bit machine, and my board is 32 cells tall… I can store one column in a single

uint32_t, rather than an array of booleans. -

I used lookup tables to improve the neighbor-counting code, rather than a nested for loop. Simply shift each column by the current y coordinate (minus 1), pull out the three least significant bits, and use that to index the lookup table. This requires 3 additions (left + center + right) with no loop overhead, rather than 9 with loops.

- To handle top-bottom wrapping, I don’t need to any funky modular arithmetic, as I had been doing before. Instead, I can use bitwise rotates! There’s no C operator that does this, but gcc actually recognizes this code:

n &= mask; return ((x >> n) | ((x << ((-n) & mask))));as “rotate

xright bynplaces”, and compiles it down to a single instruction (ROR). (maskjust enforces the bit-width of the machine.) -

I had settled on a random-generation density of 20% as being a nice value. However, I realized that the Arduino

randomfunction just calls C’srand, and mod’s the result by your requested max val. This is kind of a waste: I can just useranddirectly to generate columns from 32-bit ints, rather than setting each cell individually! This gives me a 50% bit density, however. To get down to 25% (close enough!), I generate two random numbers and bitwise-and them:0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 50% density & 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 50% density ================== 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 25% density

After many rounds of tireless and entirely unnecessary optimization, I had things down to 37 ms per generation - that’s too fast to even see (and faster than I even wanted to final product to run at). But I kept going… I made a few modifications to the drawing routines, and inlined the bit-counting functions, bringing things down to 33 ms.

Don’t get me wrong — this is plenty fast — but I was a bit curious why my seemingly-straightforward code was taking as long as it was. At 48 MHz, 33 ms per generation comes out to about 800 cycles per cell: maybe a few hundred instructions. Sure, there’s going to be some overhead outside the main loop body, but surely a few hundred instructions to count neighboring pixels and compute the next state of the cell is too much?

But just as I am writing this post, I came across my notes from an earlier test: I had been curious what the absolute maximum speed was, assuming any timing limits would probably come from the display update. Lo and behold, toggling a single pixel on and off took 28 ms per frame. No wonder I can’t get the code to run any faster!

Redoing my math from above, if the display update takes 28 ms, my code is running in 5 ms (for 33 ms total per frame). With 2048 cells on the board, that’s about 2 µs per cell. TWO! (about 96 cycles!) That makes me feel better.

(a few days later, I realized the issue was not the display, per se, but just I2C running at the default clock rate of 400 kHz. The display has 8192 pixels, so that, plus overheard, easily gets up to 28 ms. That’ll do it!)

Hardware and Enclosures

Originally I thought it would be fun to put this inside of a 3D-printed model of BMO, from Adventure Time. I’ve never seen the show but I think they’re an adorable character. However, I don’t have easy access to a 3D printer during lockdown, so for now I’m just going to solder this onto a protoboard, and figure out the enclosure later.

I also added a power button so I don’t need to unplug the Trinket to turn everything off.

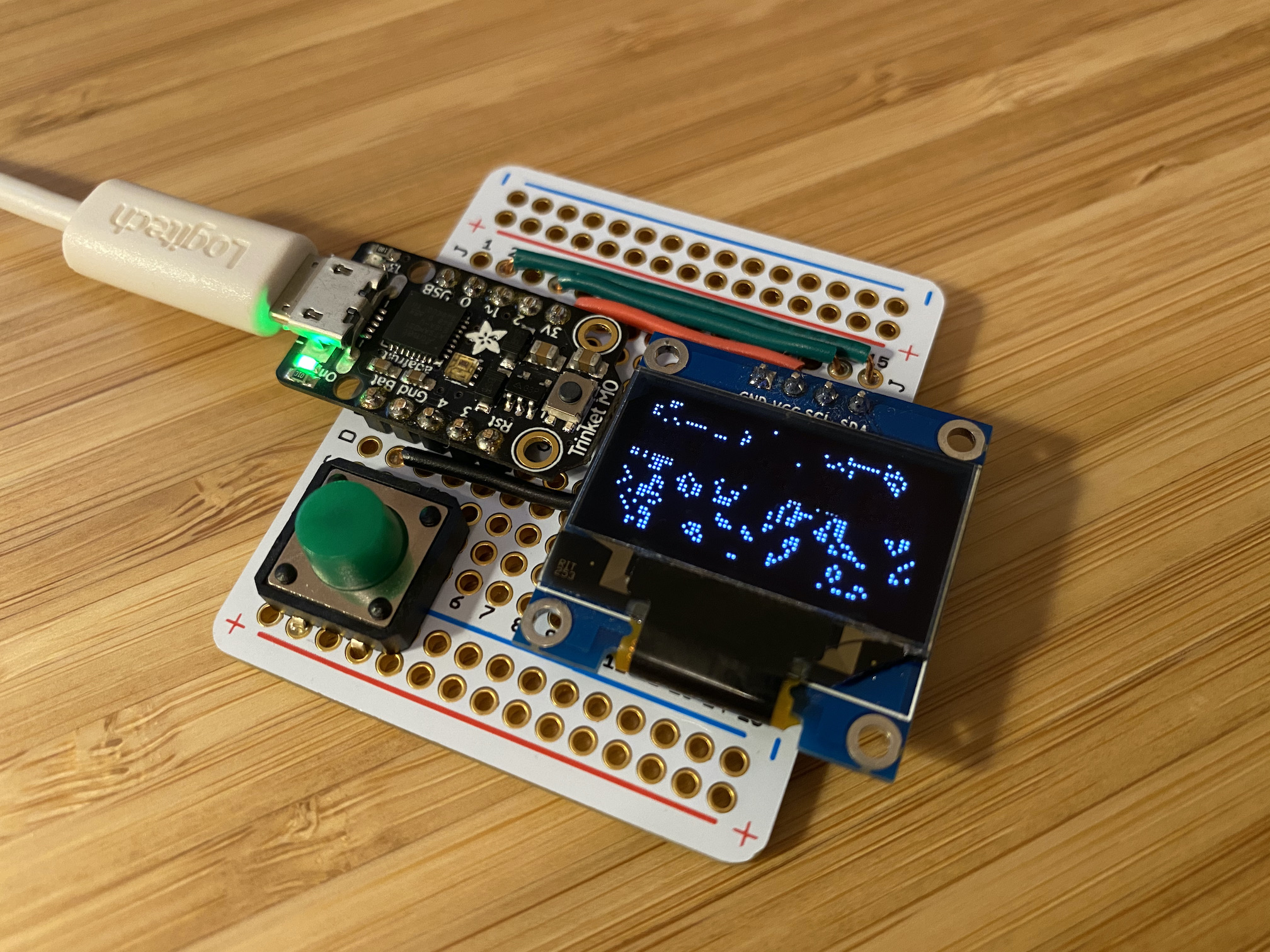

Protoboard version. Note broken corner. Black strip in middle probably due to camera shutter speed being faster than display update rate.

Protoboard version. Note broken corner. Black strip in middle probably due to camera shutter speed being faster than display update rate.

After soldering everything together on the protoboard, I realized that I was only seeing every other row of the display! At first I suspected some weird power issues, or software, or my eyes, but it turns out it’s just an unfortunate hardware failure - it seems that I broke the corner of the glass while soldering, and somehow that causes alternating rows to stop working (maybe it’s left side even, right side odd). Luckily, since I am spacing the cells out every other row, this doesn’t have a huge impact - just the text looks a little weird. But I can live with it.

Github repository here.

Update: April 2020

The end-game detection system worked quite well – but, as I knew, not on gliders. While glider infinite loops were quite rare, they ended up appearing enough to be annoying (i.e. once every day or so). I decided to implement a basic check for these cases: in addition to checking the has every 6 generations, I would also check the hash every 256 generations. (It takes 256 generations for a glider to return to its original position on my board.) Since complex loops are so rare, and they may not just be gliders, I set the program to only reset, randomly, about 1% of the time upon matching a 256-generation hash. This is very unscientific but makes me feel better that I’m more likely to see interesting looping structures emerge.

This was a relatively quick fix, but when I made it, the display broke!

In the above image, you can see that only about the top quarter of the display is working. The bottom half was, at first, displaying noise. I suspected a hardware issue, since I couldn’t get anything to work, but eventually found an old program I had written that did work. In this old program, I had manually set up all of the i2c communication, rather than using Adafruit’s library. The grid you see in the image is leftover from a prior run of that program (with Life currently attempting to run).

After many hours of pulling my hair out, I realized that somehow, I had ended up with an old version of the Adafruit SSD1306 library. This was in fact a known bug, having to do with a incorrectly sized buffer on Cortex M0 chips, that was fixed in version 2.4.1. After upgrading, everything was back to normal – and detecting looping gliders, as well.